Coexistence in an African pastoral landscape: Evidence that livestock and wildlife temporally partition water resources

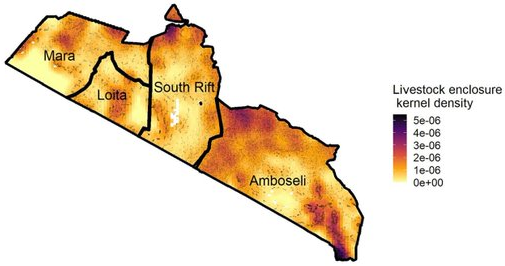

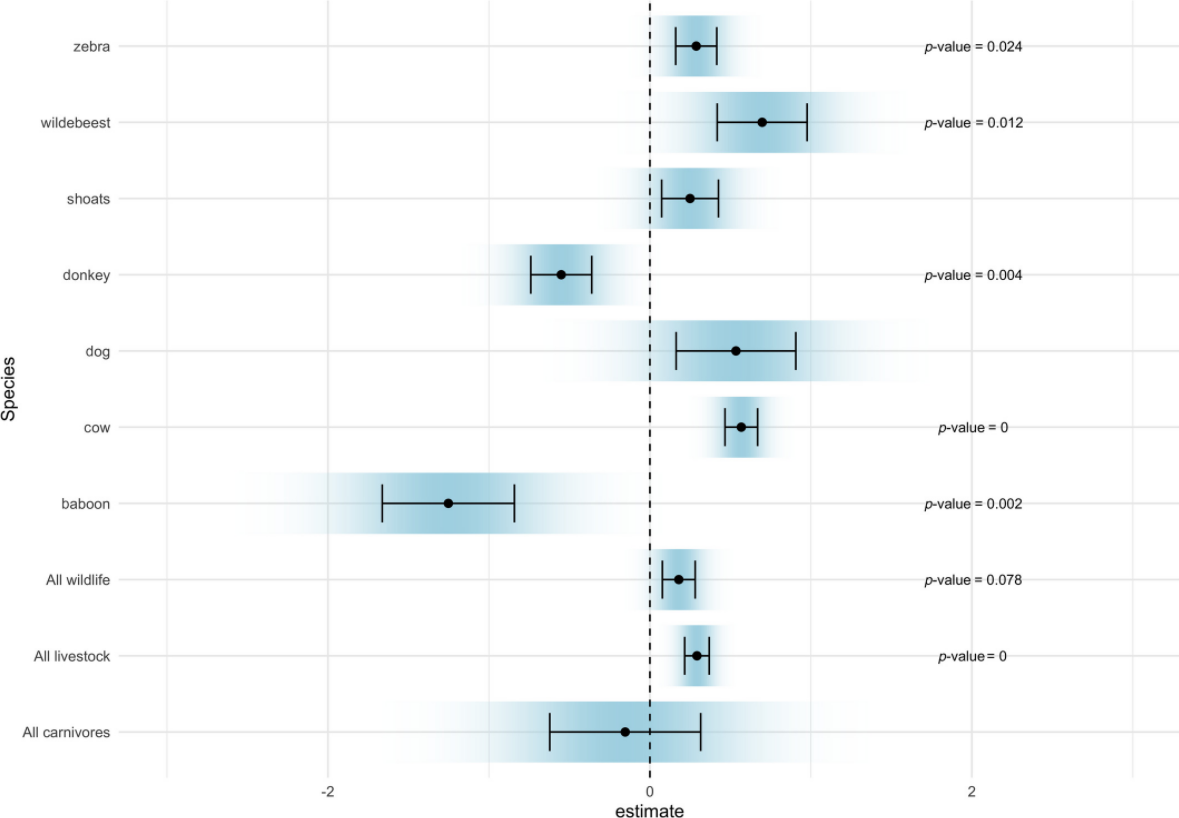

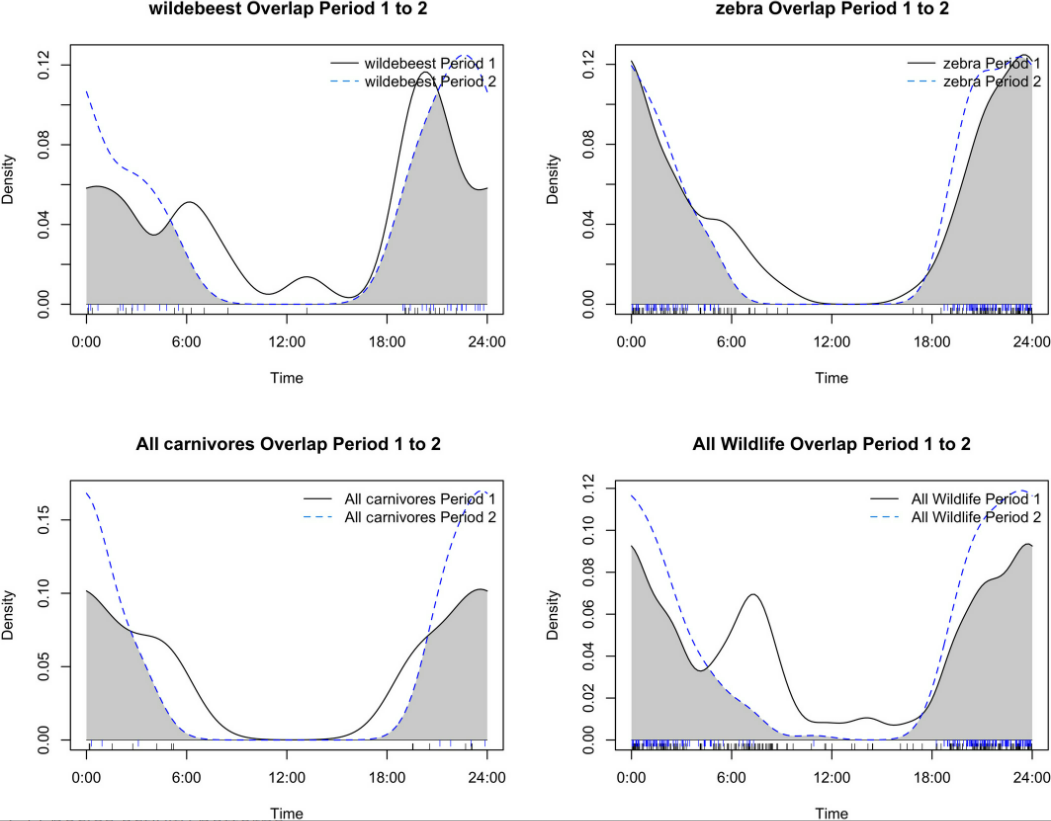

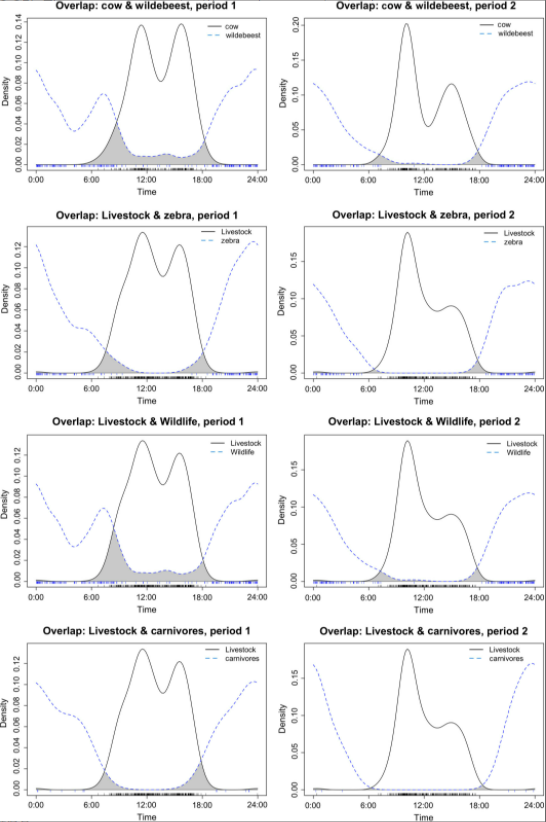

Earlier this year (2021), research that we began several years back (2013) with James Allan was finally published in the African Journal of Ecology and written up as a short blog on the University of Oxford's WildCru website . Essentially, we wanted to understand whether livestock were limiting wildlife’s ability to access water points – a vital resource for people, livestock and wildlife in drylands. What we found was that despite increases in livestock at water points when pastoralists moved into their dry season grazing areas, wildlife presence at these same water points remained steady. However, wildlife did change their behaviour and accessed these water points at night, while livestock were confined to their overnight enclosures, a local traditional practice to protect livestock from attack and theft. These mutual adaptations show that coexistence is possible even when livestock numbers increase - Wildlife adapt to the presence of people and livestock by changing their activity patterns to access water at times when competition is lowest and this is only possible because people adapt to the presence of wildlife by protecting livestock in enclosures.

Below, I've pasted the abstract (in English and French) from our paper, but please get in touch if you'd like a full copy. I've also pasted the article abstract along with some of the figures with captions explaining what each of them is showing.

I would also like to thank the people of Olkirimatian and Shompole in Southern Kenya for hosting us while we conducted this research, and for hosting many other forms of life! Thank you too to everyone involved in this research - Erin Connolly, Alice Aduda, Guy Western, Samantha Russell, Peter Tyrrell, Amy Dickman, James Allan (Research, analysis and writing) and Peter Meiponyi, Loserem Pukare, Steven Kelempu, Patrick Nkele, Albert Kuseyo (extra field work help).

Abstract: African rangelands support substantial wildlife populations alongside pastoralists and livestock. Recent wildlife declines are often attributed to competition with livestock over water and grazing, in part because livestock are thought to spatially displace wildlife. However, more evidence is needed to understand this interaction and inform rangeland management. Here, we analysed the temporal overlap between wildlife and livestock at water points in a community-governed area of Kenya's South Rift Valley, which is a dry season refuge where Maasai pastoralists, livestock and wildlife co-occur. We used camera traps to capture images at water points in two time periods: first, when nearby settlements were unoccupied, and second, as people and their herds moved into the area. We measured wildlife activity (independent detections per hour) and the difference in temporal overlap between livestock and wildlife. We found no evidence that daily wildlife activity declined despite increased human and livestock settlement. However, temporal partitioning between livestock and wildlife at watering points increased with wildlife using water resources more at night. Maasai corral livestock overnight to protect them from predation, allowing wildlife to persist in a livestock-dominated landscape. Our study demonstrates humans and wildlife co-adapting to mitigate competition for shared water resources, thereby facilitating spatial coexistence.

Abstract en français: Les pâturages africains abritent d'importantes populations d'animaux sauvages en plus des pasteurs et du bétail. Les déclins récents de la faune sont souvent attribués à la concurrence avec le bétail relative à l'eau et aux pâturages, en partie parce qu'il est présumé que le bétail déplace la faune dans l'espace. Cependant, des preuves supplémentaires sont nécessaires pour comprendre cette interaction et éclairer la gestion des pâturages. Dans cette étude, nous avons analysé le chevauchement temporel entre la faune et le bétail aux points d'eau dans une zone communautaire de la vallée du Rift Sud, au Kenya, qui est un refuge en saison sèche où cohabitent pasteurs Massaïs, bétail et faune. Nous avons utilisé des pièges photographiques pour capturer des images aux points d'eau sur deux périodes; d'abord, lorsque les points d'implantation voisins étaient inoccupées, et ensuite lorsque les gens et leurs troupeaux se sont installés dans la région. Nous avons mesuré l'activité de la faune (détections indépendantes par heure) et la différence de chevauchement temporel entre le bétail et la faune. Nous n'avons trouvé aucune preuve que l'activité quotidienne de la faune diminuait malgré l'augmentation des établissements humains et du bétail. Cependant, la répartition temporelle entre le bétail et la faune aux points d'eau a augmenté, la faune utilisant davantage les ressources en eau la nuit. Les Massaïs enferment le bétail dans des enclos pendant la nuit pour les protéger contre les prédateurs, ce qui permet à la faune de persister dans un paysage dominé par le bétail. Notre étude démontre que les humains et la faune s'adaptent mutuellement pour atténuer la concurrence relative aux ressources en eau partagées, facilitant ainsi la coexistence spatiale.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it with others who might be interested too. If you want to connect, I'm always happy to chat, so get in touch!

For those who might be interested, here are some recent publications:

- Coexistence in an African pastoral landscape: Evidence that livestock and wildlife temporally partition water resources. African Journal of Ecology Connolly, E. et al. 2021

- Defining Pathways towards African Ecological Futures. Sustainability Scheren, P. et al. 2021

- Conserving Africa's wildlife and wildlands through the COVID-19 crisis and beyond. Nature Ecology & Evolution Lindsey, P. et al. 2020

- Incorporating social-ecological complexities into conservation policy. Biological Conservation Brehony, P. et al. 2020

- Conservation from the inside-out: winning space and a place for wildlife in working landscapes. People and Nature Western, D. et al. 2020