Corpus Postgraduates: Resilience to drought in East Africa

This article was originally published in the University of Cambridge, Corpus Christi College's The Letter, Michaelmas 2017, No. 96

Dust devils swirl around, whipping up what’s left on the parched land. Emaciated carcasses dot the landscape: a cow, a zebra, a sheep, a wildebeest. People like Albert Kipanoi are taking extreme measures to survive, pulling their children out of school because they can no longer afford it, or to help look after the weak livestock. Others have travelled huge distances, at great expense, to access food and water. When the delayed rains do finally arrive, they quickly transform the landscape to one which is vivid green and alive, teeming with wildlife, livestock, and Albert’s happy family.

This is the story of East Africa’s rangelands where droughts are periodic occurrences. These rangelands are also globally renowned for their large mammal wildlife and conservation areas. However, significant changes in the social and ecological systems have occurred over the last few decades. This is the focus of my PhD, how is social and ecological resilience to drought changing, and what role is conservation playing?

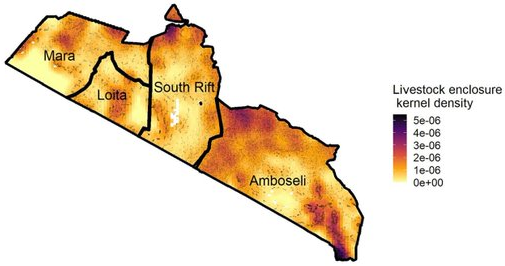

To answer these questions, I will study a semi-arid ecosystem in Southern Kenya, called the South Rift. It is an area with a rich hominid history going back as far as three and a half million years. For the last several thousand years there has been evidence of livestock rearing. The most recent inhabitants in this area are perhaps the most well-known of the African livestock rearing people, the Maasai. They play an important role managing the South Rift social-ecological system, including the incredible biological diversity. Wildlife numbers in Kenya have declined precipitously over the last three decades, but in the South Rift this trend has reversed over the last decade after the community set aside part of their communally owned land as a community conservation area. The conservation area performs an important role for the Maasai as it becomes a dry season grazing refuge for their livestock. At the same time, the establishment of a small number of tourist lodges mean that the community see some benefit from the resident wildlife.

It is in this context that drought becomes one of the most significant challenges faced by people and the environment. Drought becomes the bottleneck, when institutions and systems that were functioning, are put to the test. The perception of people in southern Kenya is that the impacts of droughts are worsening. Although there is evidence that droughts are becoming more frequent, the effects of this have been compounded by increasing habitat fragmentation; subdivision of communal land; unequal access to resources; and restrictions to mobility.

To understand the impact of these changes, my research will combine insights and methods from both ecology and social sciences. I will use satellite derived data on vegetation and land use changes; vegetation data from ground plots; and aerial census of large mammals, to understand how the ecosystem has changed over time. I will also be conducting a household survey, group discussions and interviews with people from the area. These will focus on how coping with drought and attitudes towards conservation are changing.

My research will build on the work of many others, but will use a novel and relevant approach to understanding complex systems. Insights from my research will help to focus conservation and development efforts on improving both ecological and social resilience to the effects of drought.

Post-script: I have since completed my PhD and should you wish to read some of my findings, have a look at this blog post.

Peadar’s PhD research is partially supported through small grants from the Department of Geography, The Nature Conservancy, Corpus Christi College and the Mary Euphrasia Mosley Fund. Peadar is supervised by Prof. Nigel Leader-Williams.