Long-term thinking: why carbon reduction strategies should focus on tackling cumulative emissions

A couple of years ago I attended a fascinating talk by Prof. Hilary Greaves. She made me really sit up and think about my own thoughts on individual carbon emission rates.

When it comes to looking for solutions to the climate crisis, many discussions revolve around emissions rates: reducing per capita carbon output, promoting renewable energy, and adopting low-carbon lifestyles. But what if these efforts are missing the bigger picture? According to Prof. Hilary Greaves, focusing on cumulative emissions—rather than instantaneous emissions or population size—provides a clearer understanding of how to mitigate climate change effectively.

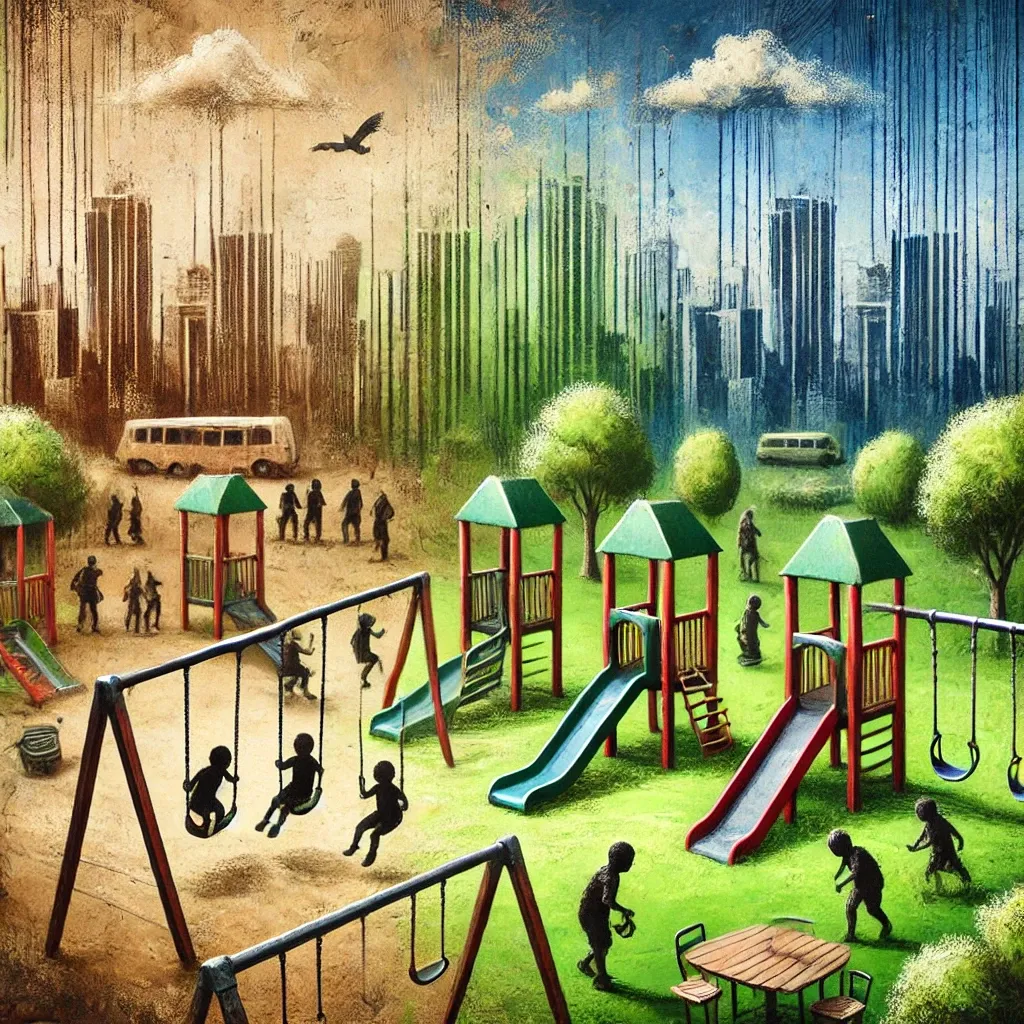

Here's a thought experiment: picture a children's playground. Over time, as fun-loving kids climb, swing, and run, the playground gradually wears out. How do you slow this process? Limiting the number of children in the playground at any one time would slow down its decay in physical time. However, ultimately, the playground only decays based on usage time, a measure of how many children use the playground over its lifetime until it has worn out from use.

Furthermore, the playground was built for children to use, so should the focus really be on delaying wear and tear over physical time?

Similarly, when it comes to carbon emissions, reducing population size at a given moment slows emissions in physical time. However, this doesn’t necessarily change the total emissions over population time, as more people into the future, even when emitting less carbon per person, can still result in the same cumulative emissions. Does this mean then, that what really matters, are cumulative emissions over population time?

Why cumulative emissions matter

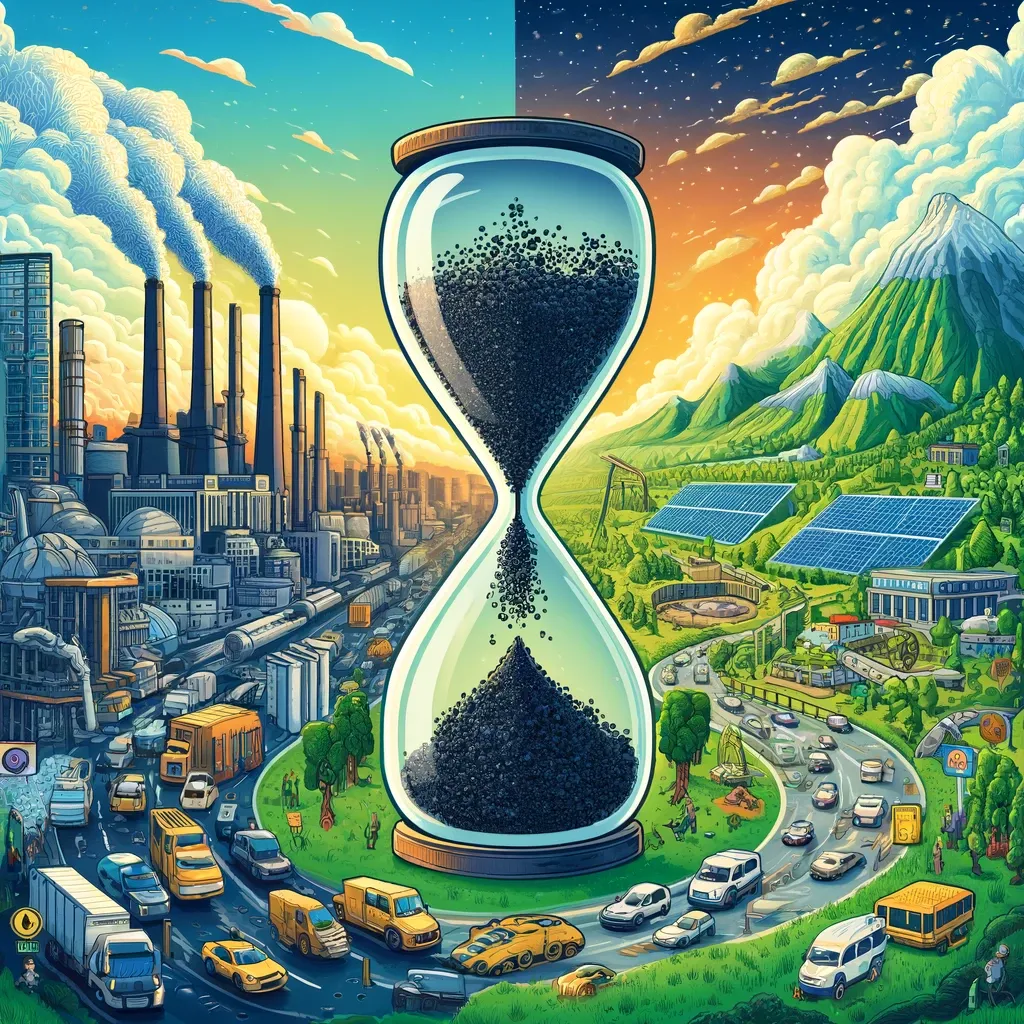

The Earth's climate responds to the total amount of greenhouse gases in, or emitted into the atmosphere over time (by humans or other means), not just the rate at which we emit them at any given moment. This means the cumulative emissions—the sum total of all emissions over history or all time—are what ultimately drive global warming, peak temperatures, and the climate crisis.

From this perspective, reducing the number of people emitting carbon at any given moment (so-called instantaneous population or rate) doesn’t necessarily solve the problem. Why? Because as long as we have the same cumulative emissions in the long run, it will not make a difference.

Imagine 500 people emitting a lifetime of carbon in 50 years versus 500 people emitting the same amount, but over 100 years. While the emissions rate differs, the total emissions are the same. Peak warming—and the associated climate impacts—remain unchanged because they depend on cumulative emissions, not when or how quickly those emissions occurred.

Is it worth it to buy time?

Reducing instantaneous emissions or slowing population growth doesn’t lower cumulative emissions, but it could buy humanity more time. For instance, by stretching out emissions, societies might have a better chance to develop innovative climate solutions, adapt to inevitable changes, and mitigate damage. However, this approach raises critical ethical questions about intergenerational equity:

Should we prioritize long-term solutions that benefit future generations, even if they come at a cost to people living today?

What trade-offs are acceptable to ensure that life remains meaningful and fulfilling despite climate impacts?

How do we address the stark inequalities, both globally and nationally, between those most responsible for emissions and those who bear the greatest costs?

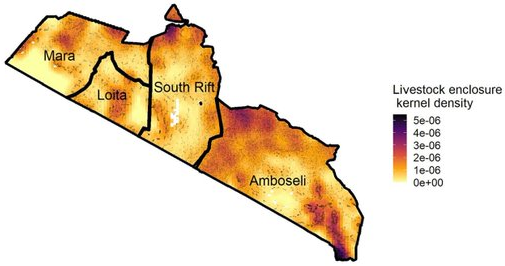

Implications for conservation and carbon credits

If one is to take this perspective seriously, it has significant implications for conservation and climate mitigation strategies like carbon credits. Efforts to preserve forests, restore ecosystems, and sequester carbon directly address cumulative emissions by offsetting the total carbon budget. Conservation projects that focus on long-term carbon storage (e.g., protecting forests for... centuries?!) are more impactful than those targeting short-term emission reductions. It is therefore critical that carbon credits tied to avoided deforestation or afforestation emphasize permanence, ensuring that stored carbon isn’t re-released into the atmosphere. On the other hand, while reducing population growth rates has often been touted as a solution to climate change, Prof. Greaves’ analysis reframes the discussion. Instead of focusing on population size as a means to lower emissions, we should shift to ensure that strategies directly address cumulative emissions.

Prof. Greaves’ insights highlight that mitigating climate change isn’t just about reducing emissions rates or population size in the short term, it’s about addressing the cumulative impacts of human activity over generations.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it with others who might be interested too. If you want to connect, I'm always happy to chat, so get in touch!