Meet the ‘Irish Attenboroughs’ who answer call of the wild

This article, which features several passionate Irish conservation scientists, including me, was originally published in The Irish Times, by Jennifer O'Connell, on the 24th of Dec, 2016. Below, I included only the section that was about me.

Peadar Brehony

PhD Student, Cambridge University and Tanzania

Asked where he thinks of as home, Peadar Brehony has to pause and think about it. “Tanzania, probably,” he answers after a moment. “But I have always had a strong sense of being Irish, too.”

He was born in Ireland, but spent his early years in Tanzania with his Irish parents, who were working in development. The family moved to Uganda when he was a toddler and then, within a few years, to Sudan and Ethiopia, before returning to Tanzania when he was in his teens. He grew up fluent in English, French and Swahili, and could converse in a number of other African dialects. “Like a lot of ‘third culture kids’, I felt very Irish, but without a strong sense of what that really meant. My impression of Ireland was mostly what I had heard from priests and nuns in Africa, so I had quite an idealised view,” he says.

His first significant experience of Ireland was as a 16-year-old, when he came “home” to do his Leaving Cert, and had an opportunity to develop “those cultural touchpoints that make you Irish”.

When he finished school in 2007, Brehony – now 28 – went on to study zoology and environmental sciences in UCC. “Initially, I wanted to be an astrophysicist, before I realised that I wouldn’t get to spend a lot of time outside,” he says.

He was hungry to see more of the world beyond Africa, and did one year of his degree at the University of California Santa Barbara, before spending time travelling in New Zealand and Western Australia. By then, he was missing the “chaos – the noise, colour and vibrancy” – of Africa, and so in 2013 he found a job as part of a marine research team working off the coast of Gabon, in Central West Africa. “Gabon has a lot of oil, so there are all these offshore oil platforms. On the one hand, you have illegal oil spills that we were trying to document, but on the other hand, the oil platforms acted as nursing grounds for a lot of marine life,” he says.

“Our job was to do surveys of the oceans to find out where key species were, including the Atlantic humpback dolphin, which is extremely endangered and rarely seen. We spent all day every day out on the water, in the biggest humpback whale breeding ground in the world, the biggest leatherback turtle breeding ground in the world. It was an incredible experience.”

The precarious journey out into the ocean every day, and the remoteness of the location, made for a tough environment, but he stayed for five months, eventually becoming the leader of his research team. By then, East Africa was calling again.

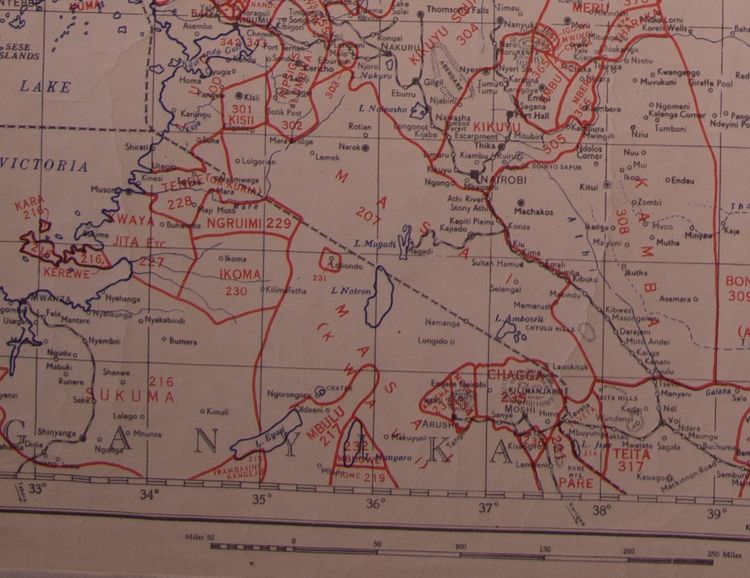

In 2014, he moved to Kenya, initially to work as a researcher on a human-lion co-existence project, and then to a job as an overall co-ordinator with the Kenya-Tanzania Borderland Conservation Initiative, a role that involved sharing research on endangered wildlife species across a number of NGOs and community landowners. He spent last year in Tanzania with the PAMS Foundation, which is working to combat elephant poaching, “using small sums of money to make a big difference.”

The hazards of the kind of work he does range from being on the receiving end of threats because of his work combatting poaching to “radio-collaring a lion, which can be scary – especially if they wake up”– to the always-present risk of being charged by elephants.

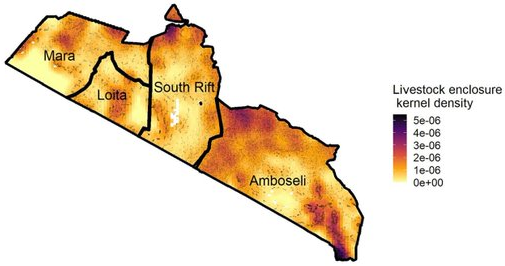

For now, Brehony is back in Europe, doing a PhD in Cambridge on the socio-ecological systems in the Borderlands area of Kenya and Tanzania. “Irish people have had a huge impact all over the globe in development. Now I think there is an incredible opportunity for us to become a global leader in conservation too. We don’t have any colonial baggage, and we tend to be good with people. In the end, conservation is all about people,” he says.

You can donate to the PAMS Foundation via its website: pamsfoundation.org