Rethinking narratives about pre-colonial Tanganyika: notes on Kjekshus' Ecology Control and Economic Development in East African History

“The basis for economic development is an ecological system controlled by man.” Kjekshus (1977)

A couple of years ago I read Helge Kjekshus' 1977 book Ecology Control and Economic Development in East African History: The Case of Tanganyika 1850-1950. It is a fascinating and well evidenced take on East Africa's pre-colonial and colonial history. I thought others who share a similar fascination for East Africa might want a snapshot of what my main takeaways from the book were.

Broadly, Kjekshus argues that a profound ecological upheaval, compounded by colonial policies, created ripple effects across social, economic, and environmental spheres, shaping the historical trajectory of the region. It also seeks to restore people as key agents of ecological change: people are doers, social, industrious, change agents.

I'll focus on a couple of key aspects of this that I found particularly interesting.

The Rinderpest Pandemic: A Turning Point in East Africa's history

A central thesis of the book is that a series of epidemics, and rinderpest in particular, did more than simply undermine existing economies; it also destabilized established authority, shifted intertribal relationships, and weakened social structures. The traditional ecological management systems, which for centuries controlled grazing and managed land, were disrupted, leading to a shift from what he saw as active community engagement to a sense of apathy.

Pre-rinderpest

Kjekshus makes the case that ecological control is key to development. He posits that a sustainable economy required an “ecosystem controlled by man.” In many places in East Africa in the pre-rinderpest era, people maintained ecological systems through fire, selective grazing, and cultivation, with an advanced knowledge of land management.

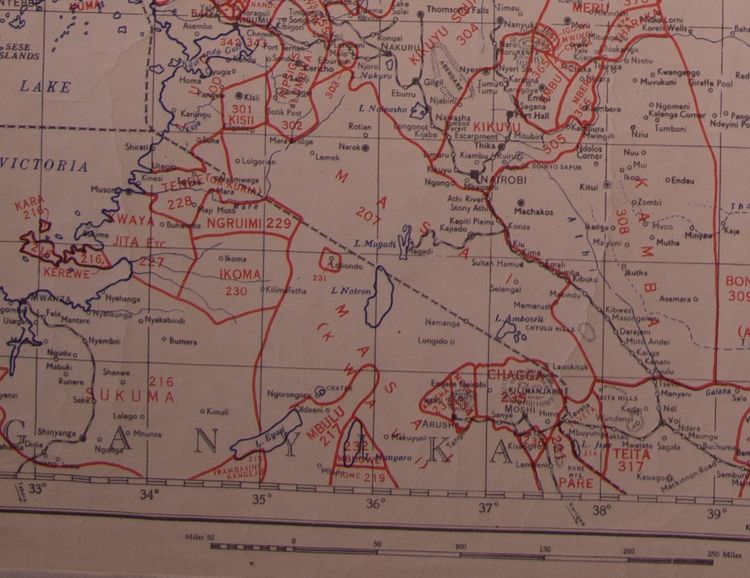

Writings of early explorers from the 19th century like Burton (1860 II:278) mention that "where the slave trade is slack, [social conditions] may, indeed, be compared advantageously with that of the peasantry in some of the richest of European countries.” Likewise, Decken writing in 1869 was struck by the abundance he encountered along the main Kilwa-Lake Nyassa road in 1860. Approximately 150 miles inland near village of Mesule up the Mbwemkuru River, he turned around along the southern edge of today’s Selous/Nyerere (devoid of most people now). Here he hunted pigeons only and complained about the absence of big game and reflected on the dense population that lived along this caravan route. He noted that “With the exception of a few places, the land was extremely well settled and cultivated in an excellent manner. Provisions were offered for sale almost everywhere along the road. Their abundance and variety reminded us of the conditions in the blessed coastal regions. People offered us goats, chicken, peas, beans, millet, sweet potatoes, flour, sugar cane, mangoes, and pistachio nuts for sale.” (Decken 1869:170). Finally, in “The role of Trypanosomiases in African Ecology” Ford (1971) revealed evidence of huge herds and general prosperity in the pre-rinderpest era.

Post-rinderpest

The rinderpest outbreak of the 1890s then had a calamitous impact and devastated many social groups, particularly those who depended on cattle-based economies, across East Africa. Kjekshus uses the accounts of a number of writers to portray rinderpest as a disaster of almost apocalyptic scale: vast herds were decimated, the pastoral Maasai and other tribes lost their main livelihoods, and famine ravaged the region. For instance Baumann (1894:31-32) wrote of:

“skeleton-like women with the madness of starvation in their sunken eyes, children looking more like frogs...’warriors’ who could hardly crawl on all fours, and apathetic, languishing elders. These people would eat anything... swarms of vultures followed them from high.”

With fewer cattle and people cultivating fields, nature took its course in "reclaiming" these lands. This created favorable conditions for the spread of the tsetse fly, which further inhibited economic recovery by rendering large areas unsuitable for agriculture or livestock. British observer Stuhlmann (1892:188) likened the impact of rinderpest on groups like the Maasai to a complete cultural breakdown, with many taking refuge among agricultural communities (for those interested also see Alan Jacobs work, and the brilliant "Being Maasai" edited by Spear and Waller).

Examples of the real implications of this include the impact on Maasai in Ngorongoro crater. According to Kjekshus rinderpest removed Maasai and their cattle from the crater in the 1890s and its pasture was then "discovered" by Siedentopf, a German settler who laid claim to one-third of the crater floor to build a cattle and ostrich ranch. By 1905 Siedentopf held more than 2,000 head of cattle and plans to expand up to 5,000 (Fuchs 1907:252). However, the Siedentoft farm was sold as enemy property after the WWI to the American millionaire, Sir Charles Ross, who kept it up as a hunting lodge for his friends.

Rinderpest only marked the beginning as it was followed by a series of calamities including smallpox (White Illness), sand-flea plague (Tunga penetrans was introduced from South America), famine and sleeping sickness. Fewer people tilling fields, fewer livestock and imperial laws against burning and hunting led to a recovery of nature. In their wake, the tsetse fly spread and put vast domains of land beyond the reach of economic activity.

Spread of Tsetse Fly and Ecological Isolation

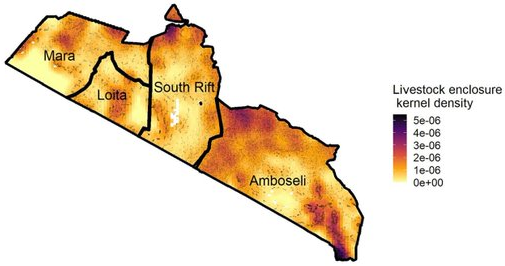

The spread of the tsetse fly played a significant role in constraining human settlements and reshaping agricultural practices. British colonial restrictions on hunting and burning exacerbated these changes. The fly thrived in areas abandoned due to rinderpest, creating what Kjekshus calls “badlands,” where human activity was limited. Locals understood the connection between tsetse flies, wildlife, and disease transmission, often avoiding these areas or crossing them at night. This local knowledge was dismissed by many European settlers, albeit not all, such as Bishop Spreiter’s (1908) who commented that locals knew more about the land than even "educated" Europeans. Another interesting anecdote came from David Livingstone (1874, II:87), who wrote “Lion’s fat is regarded as a sure preventative of tsetse ... It is smeared on the ox’s tail, and preserves hundreds of the Banyamwezi cattle in safety while going to the coast.” It is interesting to wonder to what extent this played a role in creating the current protected area network in Tanzania, which tends to coincide with the historic existence and persistence of tsetse fly...

Ultimately, this series of historical events (rinderpest, small pox, famine, tsetse fly) meant that within a few decades, much of East Africa's thriving landscapes transformed this to degradation and ruin. According to Kjekshus, this was primarily because of a lack of ecological control.

The Legacy of Colonial Policies

The colonial reorganisation of land and resources further disrupted East African communities. Among many others, the Maasai, for instance, were confined to reserves and stripped of vast grazing lands, which they had previously used and managed. These forced relocations ignored the nuanced balance Maasai pastoralists had maintained for centuries, and by diminishing their land, the colonizers impacted their social structure and subsistence. Of course state endorsed and enforced reorganisation in Tanzania continued under Nyerere's Ujamaa policy of villagisation and collective farming.

Kjekshus argues that this shift—from an active control of ecology by East Africans to imposed restrictions and ecological chaos—was pivotal in the region’s decline in prosperity.

War and Peace

Finally, one of the other interesting take-aways was around the existing narrative of perpetual tribal warfare in East Africa. Kjekshus argues that this was overstated, citing colonial records that exaggerated intertribal violence to justify interventions. While early travelers like Burton and Eliot (1905: 239) painted the Maasai as relentless aggressors, later research, like that of Kuczynski (1949), indicates that conflicts were often economic, limited to cattle raids rather than full-scale wars. Fischer (1884:62) and Jacobs (1968:27) noted that even cattle raids by the Maasai were typically small skirmishes involving fewer than 30 warriors. Kjekshus highlights how these narratives were skewed by colonial perceptions, further demonizing local customs and justifying imperial control.

A Reconsideration of East African History

So in sum, Kjekshus challenges colonial narratives of social-ecological systems in East Africa and instead restores East Africans as active agents in their own ecological and economic histories. So Tanganyika's story is not merely one of decline and destruction in the pre-colonial period, but a testament to adaptive resilience amid ecological calamity and colonial upheaval. Local practices like controlled burning, seasonal grazing, thriving cultivation and trade, reflect a sophisticated, if often overlooked, understanding of ecological management.

By viewing East Africa’s history through this ecological lens, Kjekshus encourages us to recognize the importance of human agency in environmental stewardship—a theme with enduring relevance in discussions of conservation and sustainable development today. Tanganyika’s past holds valuable lessons for understanding the profound ways that ecosystems and economies shape, and are shaped by, human action.

I hope you were as fascinated by Kjekshus' take on East African history as I was!

If you enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it with others who might be interested too. Check out some of my other posts too. If you want to connect, I'm always happy to chat, so get in touch!