Synopsis: our chapter on "Land Tenure, Livelihoods, and Conservation: Perspectives on Priorities in Tanzania’s Tarangire Ecosystem"

Together with my co-authors Alais Morindat and Makko Sinandei, we recently published a chapter where we set out to highlight approaches being taken in the Tarangire Ecosystem to combine access to secure land rights along with landscape scale access to all the resources that livestock (and wildlife) need to be productive and resilient (we call this functional heterogeneity). If you don't have access to the chapter - please reach out over researchgate.net.

The chapter was one small part of a fascinating combination of research articles in a book titled "Tarangire: Human-Wildlife Coexistence in a Fragmented Ecosystem", published by SpringerNature. The editors, Christian Kiffner, Derek Lee and Monica Bond set out to synthesise research from a number of disciplines and perspectives, to highlight the challenges in this complex domain, and to propose solutions that might work for both people and wildlife. The book includes a wealth of knowledge from a number of disciplines from anthropology to zoology, with a view to emphasising the links between seemingly disparate perspectives.

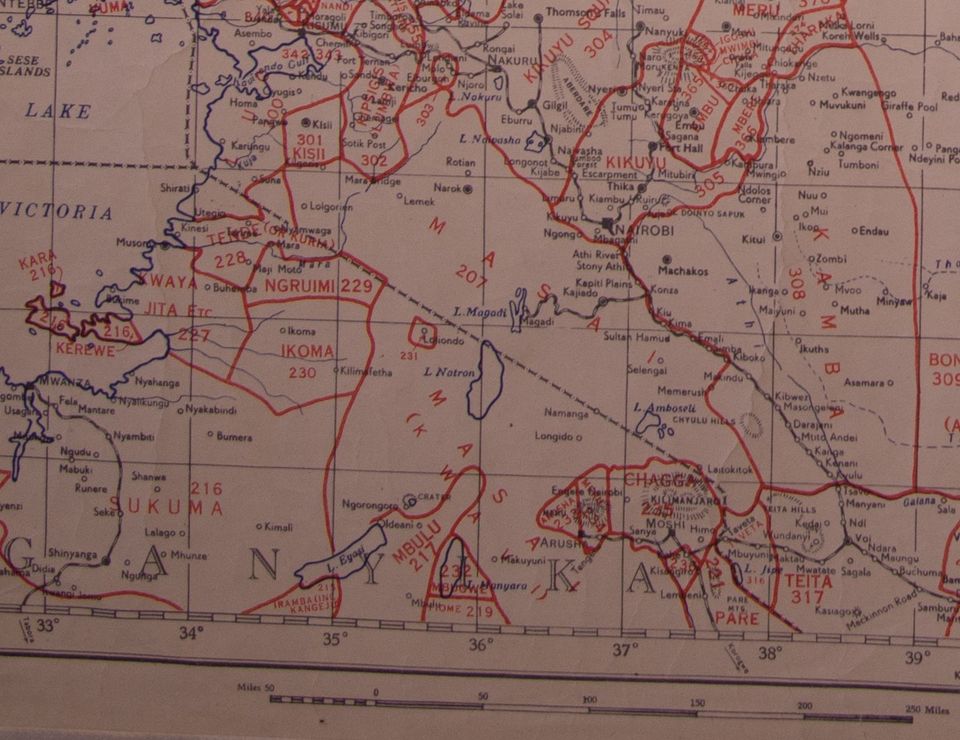

That's a little bit about the book, which I recommend you have a look at! Now I'll give a quick plain language synopsis of our chapter. In the semi-arid rangelands of the Tarangire Ecosystem in northern Tanzania, rainfall can vary by over 30% each year. Adapting to this rainfall variability and unpredictability led to the formation of unique human-livestock, human-wildlife arrangements, and instilled deep-rooted environmental knowledge in the people living in these landscapes. Mobile pastoralism, the raising of livestock who could follow rainfall patterns, was an important adaptation strategy to maximise seasonal grazing resources and to minimize risk of drought losses. Large-scale burning prevented woodland encroachment and controlled parasites, and limiting crop cultivation to small areas of predictable rainfall or irrigation allowed for vast grazing lands for livestock. This also resulted in rangelands that were suitable for large populations of wild animals.

Pastoralists, such as the Maasai people who have managed the Tarangire Ecosystem over recent centuries, rely on their livestock for cultural, spiritual, and economic reasons. Productive rangelands are key to thriving livestock, and so the Maasai herding practices aimed to ensure herd productivity and resilience, with robust systems to govern grazing commons. Complimenting these pastoral traditions, overlapping Maasai clans and age-sets allowed Maasai herds to migrate in synchrony with wild animals over a few thousand to tens of thousands of square kilometers. Likewise, complex interdependent relationship between cultivators, hunter-gatherers, and pastoralists created a network of interlinked livelihoods.

Today, processes of "modernisation" have altered these systems dramatically. The scale of mobility required to mitigate rainfall variability and droughts are no longer possible in the Tarangire Ecosystem. Land alienation in the form of national parks, large cultivation areas, and urban areas, together with land fragmentation with increased permanent settlement, rural towns, and roads all impose much greater challenges to accessing the natural resources that pastoralists, and wildlife, rely on. This can result in a negative feedback cycle as restricting access to the key grazing resources erodes the mobility and flexibility that is crucial for livestock and wildlife to thrive in semi-arid rangelands. Pastoralists are therefore often forced to convert to other livelihoods such as cultivation and wage-labour in urban areas, which then drives the cycle once more. So how can these processes be overcome?

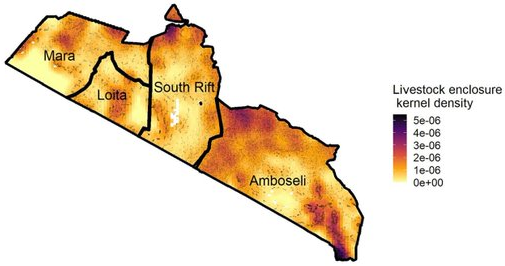

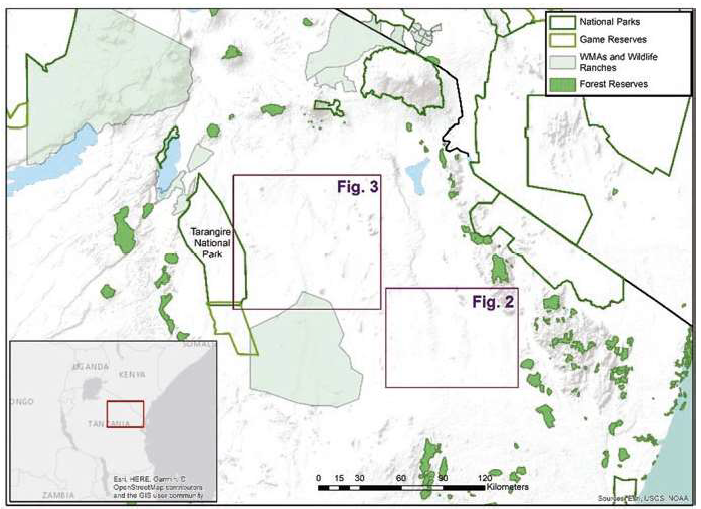

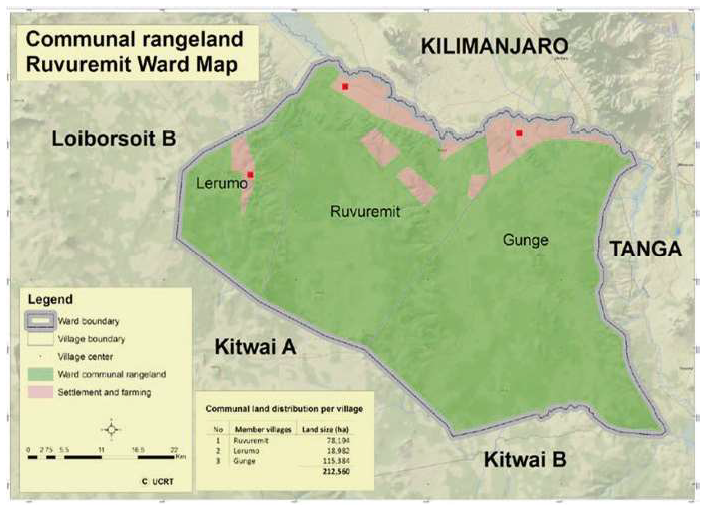

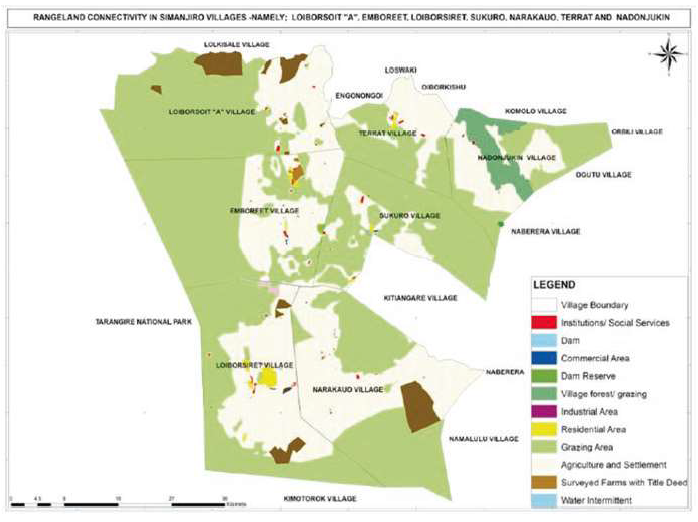

In this context, land tenure rights for pastoralists can play a critical role in securing communal grazing lands. On-going practices of NGOs working with villages across the Tarangire Ecosystem to secure rights to land and resources through spatial planning at the local scale is the first important step in this process. Careful, participatory planning processes can help rural people to decide on limits to cultivation, or to secure communal grazing lands through legal tools such as Certificate of Customary Right of Occupancy (CCROs). Local scale planning can then be scaled to up to joint-village plans (see Fig. 2) where planning can help to preserve larger swaths of rangeland. When these efforts at the local scale are repeated across large landscapes, a mosaic of land uses can help to conserve productive and resilient rangelands at the large landscape scale (see Fig. 3).

Furthermore, open rangelands that are good for livestock, are good for wildlife too. Legitimate community conservation efforts in these rangelands that work in tandem with local livelihood requirements can therefore benefit both people, livestock and wild animals.

Nevertheless, we must not be naive to political realities. As repeated events in Loliondo and Ngorongoro in Tanzania have demonstrated, there are valid reasons for Maasai pastoralists to shift away from mobile pastoralism. This is primarily because land used for cultivation can result in indisputable land ownership, providing security of land tenure, whereas common grazing lands are subject to land alienation.

Globally, at least 28% of land is effectively managed to meet global conservation goals by local communities, like those living in the Tarangire Ecosystem. The future success of conservation efforts in East Africa's rangelands depends on these communities, and we must do what we can to support them. This includes fighting against unjust processes of land alienation, particularly in the name of conservation.

If you enjoyed this post, you might also be interested in livestock and wildlife coexistence, you might also find this article on wildlife livestock temporal partitioning and this article on how what's good for livestock is good for wildlife too! Also please consider sharing these posts with others who might be interested too. If you want to connect, I'm always happy to chat, so get in touch!

This blog post was written with the help of Ùna Kinsella.